By Roselyn Du

Over the entrance to the Los Angeles Times headquarters hangs a banner with the newspaper’s promise to the world: REAL JOURNALISM, REAL IMPACT. When I visited in April 2018, the paper was still quietly situated in its historic downtown Los Angeles headquarters, right next to the City Hall and the Grand Park. Three months later, the paper moved out of its historic downtown building to a facility near Los Angeles International Airport, bringing itself closer to the rest of the nation in the latest episode in a series of ownership changes that have been going on for decades. I went there in search of a pair of data journalists, Doug Smith and Ben Welsh, who relayed to me a remarkable story of the evolution of data journalism in recent decades.

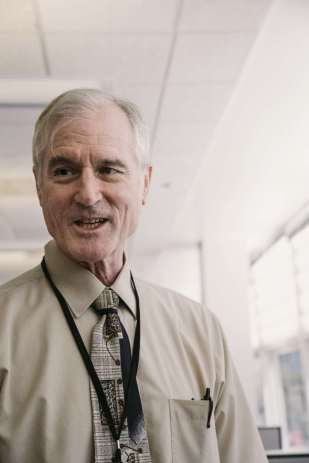

Since Smith joined the LA Times in 1970, he has covered everything from local and state government to criminal justice to politics and education. Atypical among English literature majors, Smith has never feared numbers. “My predecessor Dick O’ Reilly started the data desk in the mid 1990s, and the data desk at that time consisted of Dick and one programmer, which you can call the first original data desk,” said Smith. “When I started to do some programming at that time, I wasn’t really writing code, I was using database management.” Smith said that’s how he started to do data work there.

Smith noted that by the 1990s, government agencies in the U.S. were building their own databases with big legacy systems, such as Fortran and Cobalt, due to ballooning demands for data caused by “the development of the IBM PC, which was adopted throughout the business world and the world of the government.” However, the rapid establishment of giant databases did not seem to bring due convenience to the public. “The school district had a legacy data system, the city did, the county did, but people couldn’t navigate them and they couldn’t access to them. If reporters came to them with questions, they would say ‘Oh, here is the report.’ Well, the reports were written by bureaucrats and they never answered the questions that we had,” Smith said.

(Doug Smith: “You can’t be a reporter without being a data reporter today.”)

Obtaining ready-for-use data from an institutional source is never an easy task, even for today. But Smith refused to defer to the status quo. “I started to demand to get the underlying data, which you could, because they had it on a PC in their office, and they could just download it. And then I would write my own queries and answer my own questions,” Smith explained. “I think that motivation carries to today and is going to carry us through the future, because what we are seeing is the explosion of information, and that tools of journalism to find that information, to make sense of it, to synthesize it and to present it to readers, need to become more sophisticated to keep up with.”

When the founder of the data desk, Dick O’ Reilly, retired in 2004, Smith became the Database Editor to take charge of the data desk. He was sent to spend one week of training in SPSS. “It was a terrific class,” said Smith. “So I came back with that experience and then was sent to another one-week class for SAS, which was when I moved entirely into code world when I started writing SAS code in 2005.” That opened up a whole new world of data reporting which Smith had never imagined. “Whoah, wait a minute, every reporter needs to be a data reporter!” was his first reaction. Soon afterward, he joined NICAR (National Institute for Computer-Assisted Reporting), which he calls the most important professional event in his life. “You can’t be a reporter without being a data reporter today,” he said.

In true journalistic spirit, Smith wanted to democratize data and spread it throughout the newsroom. To do that, he and his team of dedicated reporters would need to build an infrastructure of data. However, the first challenge was to convince the editors that data journalism was something urgently needed. Frustrating though it was, when at last the day came when the editor said “oh, my god, look at this,” Smith knew he was doing the right thing. That moment came when he and his team turned in a data project about convicts being released early because of overcrowding in the jails – a project that finally got Smith’s work the recognition it deserved. Smith called that “a key moment” in data journalism.

As a first-generation data journalist, Smith took years to bring data journalism to significance at the LA Times. “You’ll notice that my byline was always last. Part of my strategy was to fight to get my byline on stories. The custom was for a data analysis to get a contributor line at the end of the story. Accepting last place on the byline was a very comfortable way to change the culture. Having editors see my name on a variety of stories was a key to gaining their respect.” The biggest project in this regard was done in the wake of the devastation of New Orleans by Hurricane Katrinia in 2005, when Smith and his team set out to compile a database of where people moving away from the city were going. “I thought that’s really interesting, so I filled a FOIA (Freedom of Information Act) request with the US Postal Service, which is a quasi-government agency,” said Smith. But the job wasn’t as simple as that – a long negotiation process ensued before the postal authority finally agreed to give them their records of address changes. From there, Smith and his team analysed the records to see the migration pattern around the country. Smith remembers clearly that the Managing Editor of the LA Times, a man named Dean Banquet who “did not care about data reporting”, came to him to say that the story worked on a personal level and meant a lot to him.

Smith participated in or led a wide variety of data-related projects, with topics ranging from LA local life to Oscar voters being overwhelmingly white and male. Of the many successes of his career, which include a Pulitzer, Smith is most proud of the report about grading and testing local teachers, which won the Philip Meyer Award. “That award actually means something to me and that’s the one award I can look back and say I really feel proud,” said Smith.

Ben Welsh is luckier than Doug Smith, in that he received a proper education in data journalism. Not just that – when he joined the LA Times in 2007, the notion that “data story is by nature not good for the print paper” had lost its ground. Even so, most senior managers still underestimated the value of data reporting, failing to realize it was already “ten years overdue.”

(Ben Welsh: “Yes, four monitors. Still not enough.”)

(Ben Welsh: “Yes, four monitors. Still not enough.”)

Since Welsh took charge of the data desk in 2012, great changes have taken place in the area of data journalism. “There is a new generation of people in our field who are more active and interested in it, who developed the skills at a young age. I think editors are now more open to it,” Welsh said. “Almost every reporter and desk now uses data in some way, even if they are just writing about data that is released by the government on the business desk, or about who scored more points in the sports game last night.” Welsh believes that the merge of print and web journalism was probably the most significant organizational change for the data team. Thanks to the merge, Welsh no longer has to shout for editorial attention for his data works or worry about having sufficient manpower to do his job. His team today boasts professionals with varying educational backgrounds, such as journalism, data management, and statistics. “There are things that we do entirely on our own, where our team is independent of the rest of the newsroom, developing idea and carrying it to fruition solo,” he said.

While SAS and Django used to be major database tools for Smith, Welsh and his associates now tend to use and even contribute to open-source software. “We are big on Python. Our team is also a heavy user and author and contributor to open-source software. I think open source software like Python and its many libraries and other things are absolutely vital and important in news,” said Welsh, adding that he is “totally fine with commercial software but it is not solving all the problems.”

Welsh thinks that frustrations still exist now, though they are not the ones Smith faced in the old days. In particular, he believes the field suffers from a shallow high-level talent pool. “I think we get great job candidates, but our issue has really been more about being able to retain and recruit that talent beyond the entry level,” he explained. “What I am really looking for in those cases is people who have shown creativity at making things happen with data.”

In a “post-truth” era, could data journalism, which requires higher level of professional skills beyond what the so-called citizen journalists possess, be a saving grace for professional journalists? Smith thinks that data and journalism are like two sides of a coin. “Data play a very important role in preventing stories that are generated by anecdotal evidence that is extreme, if you use data honestly,” he said. The other side of is, however, is when data stories are badly reported with bias or manipulation. To ensure data transparency, Smith usually includes explanatory notes in his stories.

Welsh also noted the limits and capacities of data journalism. “I don’t think we should develop any messianic complex that we are going to save the world or save the journalism, but I do think that a more scientific, transparent, convincing and persuasive presentation of news often involves data and data can help the news have all those things, or to be more of those things,” he said. Unlike Smith, who usually writes explanatory notes to go with data stories, Welsh uploads his data on GitHub, making it publicly available. “Ben has gone far beyond what I did. I am not going to GitHub – that’s one line I am not going to cross,” said Smith.

When asked for career advice to future journalists, Smith had this to say: “As the data desk becomes more complex and there is more differentiation of duties, and there is now more compartmentalization in the data world, you have to match the person you are hiring with the administrative structure of your data desk.” It takes more than “an excellent data analyst” to do the job – a good journalist, Smith says, requires “instinct”. “The psychology, the relationship with the outside world, meeting people, being gregarious and being aggressive in relationships. Those are all things that it takes to be a good reporter,” Smith declared.

Welsh echoed that newsrooms these days want more than just computer programming skills. “You also need to have creativity and show that you are able to apply those skills in a journalistic way, or in a way that is solving problem and is making things happen. Being a data journalist is often a leadership challenge.”

(Zoe Hu of HKBU contributed to this story. She also edited the videos. Natalie Ng of USC assisted in video/photo.)

For more information on the stories mentioned in this article, you can visit:

http://articles.latimes.com/2005/dec/12/nation/na-migration12

http://www.latimes.com/local/la-me-earlyreleaseproject-story.html

http://projects.latimes.com/value-added/teacher/guadalup-arias/ (This is a link to an individual teacher showing the visualization created for the second year.)

http://www.latimes.com/local/la-me-teachers-value-20100815-story.html (This is the main story. Unfortunately, there seems to be a problem with the display. But it’s still readable.)